You know about numbers as you have learnt to count but what is number system. You know how to count, but what about splitting a pizza, measuring a circle, or finding a square’s diagonal? Numbers evolved to solve real problems—fractions for sharing, negatives for debts, and never-ending numbers like π, √2, and √3 that can’t be written as simple fractions. Some numbers end neatly while others run forever without pattern, and understanding number system is important to understand secrets of universe.

1.1 Classification of Numbers

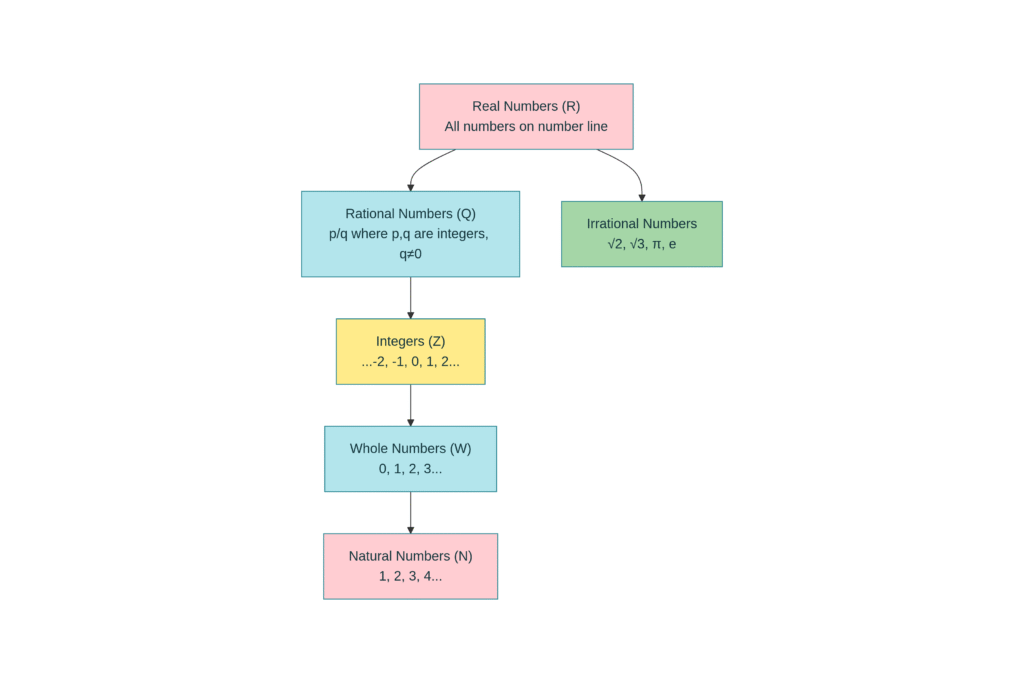

Understanding the Bag of Numbers

Let’s understand how different types of numbers relate to each other:

Natural Numbers (N): These are the counting numbers.

- N = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …}

- Used for counting objects

- Do NOT include zero

Whole Numbers (W): These are natural numbers plus zero.

- W = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, …}

- Include zero but no negative numbers

Integers (Z): These include positive, negative, and zero.

- Z = {…, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …}

- The symbol Z comes from the German word “zahlen” meaning “to count”

Rational Numbers (Q): These can be expressed as a ratio of two integers.

- Definition: A number r is called a rational number if it can be written as p/q, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0

- The symbol Q comes from the word “quotient”

- Examples: 3/4, -5/2, 7/1 (which is 7), 0/5 (which is 0)

- Important: Every natural number, whole number, and integer is also a rational number!

Why do we require q ≠ 0? Division by zero is undefined in mathematics, so we must exclude it.

Equivalent Representations of Rational Numbers

A single rational number can be written in many forms:

1/2 = 2/4 = 3/6 = 4/8 = 5/10 = 20/50

All these fractions are equivalent! However, when we represent a rational number in standard form, we use the lowest terms (simplest form) where p and q have no common factors other than 1. This is called a co-prime representation.

Example Problems:

Problem 1: Are the following statements true or false? Give reasons.

- (i) Every whole number is a natural number.

- (ii) Every integer is a rational number.

- (iii) Every rational number is an integer.

Solution:

- (i) FALSE — Zero is a whole number, but not a natural number.

- (ii) TRUE — Every integer m can be written as m/1, which is in the form p/q where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0. So every integer is rational.

- (iii) FALSE — The number 3/5 is rational, but it is not an integer.

Problem 2: Find five rational numbers between 1 and 2.

Solution – Method 1 (Using Average):

To find a rational number between two numbers r and s, we use: (r + s)/2

- Between 1 and 2: (1 + 2)/2 = 3/2 = 1.5

- Between 1 and 3/2: (1 + 3/2)/2 = 5/4 = 1.25

- Between 3/2 and 2: (3/2 + 2)/2 = 7/4 = 1.75

- Between 5/4 and 3/2: (5/4 + 3/2)/2 = 11/8 = 1.375

- Between 7/4 and 2: (7/4 + 2)/2 = 15/8 = 1.875

Five rational numbers: 5/4, 11/8, 3/2, 7/4, 15/8

Solution – Method 2 (Using Common Denominator):

Write 1 and 2 with denominator (n+1) where n=5:

- 1 = 6/6

- 2 = 12/6

Numbers between them: 7/6, 8/6, 9/6, 10/6, 11/6

Key Insight: There are infinitely many rational numbers between any two given rational numbers!

Exercise 1.1 – Answers

Question 1: Is zero a rational number? Can you write it in the form p/q where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0?

Answer: YES! Zero is a rational number because 0 = 0/1 = 0/2 = 0/3… (where p = 0 and q is any non-zero integer)

Question 2: Find six rational numbers between 3 and 4.

Answer: Using the common denominator method, write 3 = 21/7 and 4 = 28/7

Numbers between them: 22/7, 23/7, 24/7, 25/7, 26/7, 27/7

(Note: 22/7 ≈ 3.14 is a famous approximation of π!)

Question 3: Find five rational numbers between -3/5 and 4/5.

Answer: Convert to common denominator (multiply by 6):

- -3/5 = -18/30

- 4/5 = 24/30

Five numbers: -17/30, -10/30, 0, 10/30, 18/30 (or simplified: -17/30, -1/3, 0, 1/3, 3/5)

Question 4: State whether true or false. Give reasons.

- (i) Every natural number is a whole number.

- (ii) Every integer is a whole number.

- (iii) Every rational number is a whole number.

Answer:

- (i) TRUE — All natural numbers {1, 2, 3, …} are contained in whole numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, …}

- (ii) FALSE — Negative integers like -5, -100 are not whole numbers

- (iii) FALSE — Rational numbers like 1/2, 3/4, -5/3 are not whole numbers

1.2 Irrational Numbers

What are Irrational Numbers?

So far, we’ve seen that many numbers can be expressed as p/q. But are there numbers that CANNOT be written in this form?

Historical Discovery:

The ancient Pythagoreans (followers of Pythagoras, around 400 BC) were shocked to discover numbers that could not be expressed as ratios of integers! These numbers were called irrational numbers (literally meaning “not rational”).

Legend has it that Hippacus of Croton discovered that √2 is irrational. There are many myths about his fate for this discovery—some say he was drowned or exiled from the Pythagorean community for revealing this secret!

Formal Definition:

A number s is called irrational if it cannot be written in the form p/q, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.

Examples of Irrational Numbers

Common Irrational Numbers:

- √2 = 1.41421356…

- √3 = 1.73205080…

- √5 = 2.23606797…

- π = 3.14159265… (ratio of circumference to diameter)

- e = 2.71828182… (base of natural logarithm)

- 0.10110111011110… (non-repeating pattern)

Important: The decimal expansion of irrational numbers:

- Never terminates (doesn’t end)

- Never repeats (the pattern never becomes regular)

Locating Irrational Numbers on the Number Line

Locating √2:

Using the Pythagorean theorem:

- Draw a square OABC with each side = 1 unit

- The diagonal OB has length √(1² + 1²) = √2

- Place O at zero on the number line

- Using a compass with center O and radius OB

- Draw an arc that intersects the number line at point P

- Point P represents √2 ≈ 1.414

Locating √3:

- Start from the point where √2 is marked (point P)

- Draw a perpendicular line of length 1 unit from this point

- Use Pythagorean theorem: (√2)² + 1² = 2 + 1 = 3

- So the hypotenuse has length √3

- Transfer this length to the number line using a compass

- Point Q now represents √3 ≈ 1.732

The Beautiful Square Root Spiral:

You can continue this process indefinitely to locate √4, √5, √6, and so on. When you connect these points with arcs, you create a beautiful spiral pattern called the “square root spiral”! This is a classroom activity that shows how irrational numbers continue infinitely on the number line.

Real Numbers: The Complete Picture

Definition: The collection of all rational and irrational numbers together form the set of Real Numbers (R).

Key Property:

- Every point on the number line corresponds to exactly ONE real number

- Every real number corresponds to exactly ONE point on the number line

This one-to-one correspondence between points and real numbers is why we call it the “Real Number Line.”

Exercise 1.2 – Answers

Question 1: State true or false. Justify your answers.

- (i) Every irrational number is a real number.

- (ii) Every point on the number line is of the form √m, where m is a natural number.

- (iii) Every real number is an irrational number.

Answer:

- (i) TRUE — Real numbers = Rational numbers + Irrational numbers. So all irrationals are real.

- (ii) FALSE — Points can represent rational numbers too (like 1/2, 3/4), which are not square roots of natural numbers.

- (iii) FALSE — Real numbers include both rational (like 5/2) and irrational numbers.

Question 2: Are the square roots of all positive integers irrational? If not, give an example.

Answer: NO. Perfect squares have rational square roots.

- √1 = 1 (rational)

- √4 = 2 (rational)

- √9 = 3 (rational)

- √16 = 4 (rational)

But √2, √3, √5, √6, √7, √8, √10… are irrational.

Question 3: Show how √5 can be represented on the number line.

Answer:

- Start with √2 on the number line

- Draw a perpendicular of length √3 from the √2 point

- Find the hypotenuse: √(2 + 3) = √5

- Use a compass to transfer this length to the number line

- The intersection point represents √5

1.3 Real Numbers and Their Decimal Expansions

Decimals Reveal Number Type!

By examining the decimal expansion of a number, we can determine whether it’s rational or irrational. This is one of the most elegant ways to distinguish between these types of numbers.

Decimal Expansions of Rational Numbers

Let’s divide some rational numbers and observe the pattern:

Example 1: 10/3

- 10 ÷ 3 = 3.333…

- Remainders: 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

- The remainder 1 repeats forever

- Result: Non-terminating recurring decimal

Example 2: 7/8

- 7 ÷ 8 = 0.875

- Remainders: 7, 6, 4, 0

- The remainder becomes 0

- Result: Terminating decimal (stops after 3 decimal places)

Example 3: 1/7

- 1 ÷ 7 = 0.142857142857…

- Remainders: 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5, 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5… (repeats!)

- The block “142857” repeats

- Result: Non-terminating recurring decimal

Pattern in Rational Number Decimals:

Key Observation:

- The remainder either becomes 0 (terminating) OR repeats

- Number of distinct remainders < divisor

- Non-terminating decimals show a repeating block of digits

Notation for Repeating Decimals:

- 10/3 = 3.3̄ (the bar indicates 3 repeats)

- 1/7 = 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄ (the block 142857 repeats)

- 11/4 = 2.7̄5̄ (the block 75 repeats after 2)

Converting Repeating Decimals to Fractions

Example 1: Convert 0.3̄ to fraction form

Let x = 0.333…

Then 10x = 3.333…

Subtracting: 10x – x = 3.333… – 0.333…

9x = 3

x = 3/9 = 1/3

Example 2: Convert 1.2̄7̄ to fraction form (27 repeating)

Let x = 1.272727…

The repeating block has 2 digits, so multiply by 100:

100x = 127.272727…

Subtracting: 100x – x = 127.272727… – 1.272727…

99x = 126

x = 126/99 = 14/11

Example 3: Convert 0.2̄3̄5̄ to fraction form (35 repeats, 2 doesn’t)

Let x = 0.235353…

Multiply by 10 (since 2 doesn’t repeat): 10x = 2.35353…

Multiply by 1000 (for the 2-digit repeating part): 1000x = 235.35353…

Subtracting: 1000x – 10x = 235.35353… – 2.35353…

990x = 233

x = 233/990

Important Rule for Rational Numbers:

Theorem: A number is rational if and only if its decimal expansion is either:

- Terminating (like 0.875)

- Non-terminating recurring (like 0.3̄ or 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄)

Conversely, if you see a decimal that terminates or repeats, it’s definitely rational!

Decimal Expansions of Irrational Numbers

The Key Difference:

Irrational numbers have decimal expansions that are:

- Non-terminating (never ends)

- Non-recurring (the pattern never repeats)

Examples:

- √2 = 1.41421356237309504880…

- √3 = 1.73205080756887729352…

- π = 3.14159265358979323846…

- 0.10110111011110… (designed to never repeat)

Notice how the digits continue forever with no repeating pattern!

Theorem: A number is irrational if and only if its decimal expansion is non-terminating and non-recurring.

Historical Perspectives on π

The famous number π (ratio of circumference to diameter) has fascinated mathematicians for millennia:

- Archimedes (287-212 BCE): Proved that 3.140845 < π < 3.142857

- Aryabhata (476-550 CE): Indian mathematician found π ≈ 3.1416 (accurate to 4 decimal places)

- Modern era: Using computers, π has been calculated to over 1.24 trillion decimal places!

Interestingly, the Sulbasutras (ancient Indian mathematical texts, 800-500 BCE) approximated √2 as:

√2 ≈ 1 + (1/3) + (1/3×4) – (1/3×4×34) = 1.4142156…

This matches the modern value to five decimal places!

Finding Irrational Numbers Between Rationals

Question: Can we find an irrational number between 1/7 and 2/7?

Solution:

- 1/7 = 0.142857…

- 2/7 = 0.285714…

An irrational number between them: 0.150150015000150000…

This number has a non-repeating pattern (notice the increasing zeros), so it’s irrational!

Conclusion: Between ANY two rational numbers, there exist infinitely many irrational numbers!

Exercise 1.3 – Answers

Question 1: Write in decimal form and identify the type:

- (i) 36/100 = 0.36 — Terminating

- (ii) 1/11 = 0.0̄9̄ — Non-terminating recurring

- (iii) 4/1 = 4.0 — Terminating

- (iv) 13/11 = 1.1̄8̄ — Non-terminating recurring

- (v) 1/8 = 0.125 — Terminating

- (vi) 400/2 = 200.0 — Terminating

Question 2: Can you predict decimal expansions of 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, 5/7, 6/7 without division?

Answer: YES! Since 1/7 = 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄, observe the remainders {1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5}:

- 2/7 = 0.2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄4̄

- 3/7 = 0.4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄

- 4/7 = 0.5̄7̄1̄4̄2̄8̄

- 5/7 = 0.7̄1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄

- 6/7 = 0.8̄5̄7̄1̄4̄2̄

(Each is a cyclic shift of the block!)

Question 3: Express as p/q:

- (i) 0.6̄ = 6/9 = 2/3

- (ii) 0.4̄7̄ = 47/99

- (iii) 0.0̄0̄1̄ = 1/999

Question 4: Express 0.9̄9̄9̄… as p/q. Are you surprised?

Solution:

Let x = 0.999…

10x = 9.999…

10x – x = 9

9x = 9

x = 1

Answer: 0.999… = 1

Surprise? Yes! This shows that 0.999… (repeating) is exactly equal to 1, not just approximately!

Question 5: Maximum number of digits in repeating block of 1/17?

Answer: Maximum = 16 (divisor – 1). Actual: 1/17 = 0.0̄5̄8̄8̄2̄3̄5̄2̄9̄4̄1̄1̄7̄6̄4̄7̄ (16 repeating digits)

Question 6: Property of q for terminating decimals?

Answer: For p/q to terminate, q must have only factors of 2 and 5.

- 1/8 = 0.125 ✓ (8 = 2³)

- 3/4 = 0.75 ✓ (4 = 2²)

- 7/6 doesn’t terminate ✗ (6 = 2×3, has factor 3)

Question 7: Three non-terminating non-recurring decimals:

- 0.10100100010…

- 0.20200200020…

- 0.303003000300003…

Question 8: Three irrational numbers between 5/7 and 9/11:

- 0.7̄1̄8̄9̄2̄8̄… ≈ 0.719 (1/7 ≈ 0.714, 9/11 ≈ 0.818)

- 0.7502500250025…

- 0.7606000600060…

Question 9: Classify as rational or irrational:

- (i) √23 — Irrational (23 is not a perfect square)

- (ii) √225 = 15 — Rational

- (iii) 0.3796 — Rational (terminating)

- (iv) 7.478478… = 7.4̄7̄8̄ — Rational (repeating)

- (v) 1.101001000100001… — Irrational (increasing zeros, non-repeating)

1.4 Operations on Real Numbers

Do Irrational Numbers Follow Our Laws?

Great news! Irrational numbers also satisfy:

- Commutative law: a + b = b + a and ab = ba

- Associative law: (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) and (ab)c = a(bc)

- Distributive law: a(b + c) = ab + ac

However, when we ADD, SUBTRACT, MULTIPLY, or DIVIDE irrational numbers, the result might be rational or irrational!

Examples:

- √2 + √2 = 2√2 (irrational)

- √2 – √2 = 0 (rational!)

- √3 × √3 = 3 (rational!)

- (√17/6) ÷ (√17/6) = 1 (rational!)

Important Rules:

Rule 1: (Rational) + (Irrational) = Irrational

- Example: 2 + √3 = 2 + √3 (irrational)

Rule 2: (Non-zero Rational) × (Irrational) = Irrational

- Example: 7 × √5 = 7√5 (irrational)

Rule 3: (Irrational) + (Irrational) = Could be Rational or Irrational

- Example: √2 + √2 = 2√2 (irrational)

- Example: √5 – √5 = 0 (rational)

Useful Identities for Square Roots

For positive real numbers a and b:

Identity 1: √(ab) = √a × √b

- Example: √12 = √(4×3) = √4 × √3 = 2√3

Identity 2: √(a/b) = √a / √b (b ≠ 0)

- Example: √(2/9) = √2 / √9 = √2 / 3

Identity 3: (√a – √b)(√a + √b) = a – b

- Example: (√5 – √3)(√5 + √3) = 5 – 3 = 2

Identity 4: (√a + √b)² = a + 2√(ab) + b

- Example: (√3 + √2)² = 3 + 2√6 + 2 = 5 + 2√6

Simplifying Square Root Expressions

Example 1: Simplify √75

- √75 = √(25 × 3) = √25 × √3 = 5√3

Example 2: Simplify 3√7 + 2√7

- 3√7 + 2√7 = (3 + 2)√7 = 5√7

Example 3: Simplify (√5 + √5)/(√5 – √5)

Wait—the denominator is 0! This expression is undefined.

Example 4: Simplify (3√7)/(2√7)

- = (3/2) × (√7/√7)

- = (3/2) × 1

- = 3/2

Example 5: Simplify √20 + √45 – √80

- √20 = √(4×5) = 2√5

- √45 = √(9×5) = 3√5

- √80 = √(16×5) = 4√5

- Result: 2√5 + 3√5 – 4√5 = √5

Example 6: Simplify (11 – √7)(11 + √7)

- Using Identity 3: a = 11, b = √7

- = 11² – (√7)²

- = 121 – 7

- = 114

Rationalizing the Denominator

When a fraction has a square root in the denominator, it’s often useful to eliminate it. This process is called rationalizing the denominator.

Case 1: Single Square Root in Denominator

Example: Rationalize 1/√2

- Multiply by √2/√2:

- (1/√2) × (√2/√2) = √2/2

Case 2: Square Root Plus/Minus Another Number

Example: Rationalize 1/(√2 + √3)

- Use Identity 3: multiply by (√2 – √3)/(√2 – √3)

- = [1 × (√2 – √3)] / [(√2 + √3)(√2 – √3)]

- = (√2 – √3) / (2 – 3)

- = (√2 – √3) / (-1)

- = √3 – √2

Example: Rationalize 1/(2 – √3)

- Multiply by (2 + √3)/(2 + √3):

- = [1 × (2 + √3)] / [(2 – √3)(2 + √3)]

- = (2 + √3) / (4 – 3)

- = 2 + √3

Exercise 1.4 – Answers

Question 1: Classify as rational or irrational:

- (i) √27 / √3 = √(27/3) = √9 = 3 — Rational

- (ii) √8 / √2 = √(8/2) = √4 = 2 — Rational

- (iii) 2π / (7π) = 2/7 — Rational (π cancels!)

- (iv) √2 (obviously) — Irrational

Question 2: Simplify each expression:

- (i) (3√3 + 2√3) = 5√3

- (ii) (√3 – √3) = 0

- (iii) (√5 + √2)(√5 – √2) = 5 – 2 = 3

- (iv) (√5 – √2) / (√5 + √2) = (5 – 2√10 + 2) / (5 – 2) = (7 – 2√10) / 3

Question 3: The π Paradox

- Circumference = πd, so π = C/d

- But π is irrational, while C/d looks like a ratio!

- Resolution: While π IS a ratio of C to d, we cannot express this as a ratio of two integers. The circumference itself is irrational when the diameter is rational!

Question 4: Represent 9.3 on the number line

- Mark 9.3 units from origin

- Alternatively: 9.3 = 93/10 (between 9 and 10, closer to 9)

Question 5: Rationalize denominators:

- (i) 1/√7 = √7/7

- (ii) 1/(√7 + √6) = (√7 – √6)/(7-6) = √7 – √6

- (iii) 1/(√5 + √2) = (√5 – √2)/(5-2) = (√5 – √2)/3

- (iv) 5/(√5 – √2) = [5(√5 + √2)] / [(√5 – √2)(√5 + √2)] = [5(√5 + √2)] / 3

1.5 Laws of Exponents for Real Numbers

Review of Basic Exponent Laws

For natural numbers a, m, n:

Law 1: a^m × a^n = a^(m+n)

- Example: 2³ × 2⁵ = 2⁸ = 256

Law 2: (a^m)^n = a^(mn)

- Example: (3²)⁴ = 3⁸ = 6561

Law 3: a^m / a^n = a^(m-n) (when m > n)

- Example: 5⁷ / 5³ = 5⁴

Law 4: (ab)^m = a^m × b^m

- Example: (2×3)⁴ = 2⁴ × 3⁴

Extending to Negative Exponents

From Law 3, if m < n:

- a^m / a^n = 1 / a^(n-m) = a^(-(n-m))

Therefore: a^(-n) = 1 / a^n

Examples:

- 2^(-3) = 1/8

- 5^(-2) = 1/25

Fractional Exponents

Understanding a^(1/n):

If a > 0 and n is a positive integer, then:

- a^(1/n) = ⁿ√a (the nth root of a)

- Because: (a^(1/n))^n = a

Examples:

- 9^(1/2) = √9 = 3

- 8^(1/3) = ³√8 = 2

- 16^(1/4) = ⁴√16 = 2

- 32^(1/5) = ⁵√32 = 2

Understanding a^(m/n):

a^(m/n) = (a^m)^(1/n) = ⁿ√(a^m)

Or equivalently: a^(m/n) = (a^(1/n))^m = (ⁿ√a)^m

Example: 8^(2/3)

- Method 1: 8^(2/3) = (8²)^(1/3) = 64^(1/3) = 4

- Method 2: 8^(2/3) = (8^(1/3))² = 2² = 4

Extended Laws of Exponents

For any real number a > 0 and rational numbers p, q:

Law 1: a^p × a^q = a^(p+q)

Law 2: (a^p)^q = a^(pq)

Law 3: a^p / a^q = a^(p-q)

Law 4: (ab)^p = a^p × b^p

Exercise 1.5 – Answers

Question 1: Find:

- (i) (2³ × 2⁵) = 2⁸ = 256 [or using law: 2^(3+5) = 2⁸]

- (ii) (3^(2/5)) = ⁵√(3²) = ⁵√9

- (iii) (125^(1/3)) = ³√125 = 5

- (iv) (125^(1/3)) [same as above] = 5

Question 2: Find:

- (i) (2^(1/3) × 2^(5)) = 2^(1/3 + 5) = 2^(16/3)

- (ii) (32^(2/5)) = (2⁵)^(2/5) = 2² = 4

- (iii) (1/125)^(1/3) = 1/5

Question 3: Simplify:

- (i) (2^(1/2) × 2^(1/3)) = 2^(1/2 + 1/3) = 2^(5/6)

- (ii) (3^(2/5)) [already simplified]

- (iii) (1/125)^(1/3) = 1/5

- (iv) (125^(1/3))^2 = 5² = 25

Question 4: Apply Laws:

- (i) 7^(3) × 7^(-3) = 7^(3-3) = 7⁰ = 1

- (ii) (7^(1/3))/(7^(1/3)) = 7^(1/3 – 1/3) = 7⁰ = 1

- (iii) (1/7^(2)) × (1/1^(1/4)) = 7^(-2) × 1 = 1/49

- (iv) (7^(2) × 8^(2)) = (7 × 8)² = 56²

Chapter Summary

Key Definitions

- Rational Number: Can be expressed as p/q where p, q are integers and q ≠ 0

- Irrational Number: Cannot be expressed as p/q (includes √2, √3, π, e)

- Real Number: Any rational or irrational number

- Decimal Expansion:

- Rational: Terminating or non-terminating recurring

- Irrational: Non-terminating non-recurring

Important Properties

- All natural numbers, whole numbers, and integers are rational

- There are infinitely many rationals between any two rationals

- There are infinitely many irrationals between any two rationals

- Rational + Irrational = Irrational (when rational ≠ 0)

- The number line contains every real number, and every real number corresponds to a point on the line

Simplification Rules

- √(ab) = √a × √b

- √(a/b) = √a / √b

- (√a – √b)(√a + √b) = a – b

- (√a + √b)² = a + 2√(ab) + b

- √a^(2n) = a^n (for positive a)

Exponent Laws (a > 0, p, q rational)

- a^p × a^q = a^(p+q)

- (a^p)^q = a^(pq)

- a^p / a^q = a^(p-q)

- (ab)^p = a^p × b^p

- a^(-p) = 1/a^p

- a^(p/q) = ⁿ√(a^m) where p/q = m/n

Quick Reference: Number Systems Comparison Table & Summary

Visual Comparison of Number Systems

| Feature | Natural Numbers | Whole Numbers | Integers | Rational Numbers | Irrational Numbers | Real Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | N | W | Z | Q | — | R |

| Examples | 1, 2, 3, 99 | 0, 1, 2, 99 | -5, 0, 7, 100 | -3/2, 0, 5/4, 7 | √2, π, e, √5 | All of above |

| Include Zero? | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Include Negatives? | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES (some) | YES |

| Can write as p/q? | YES (n/1) | YES (n/1) | YES (n/1) | YES | NO | Mix |

| Decimal Type | Terminating | Terminating | Terminating | Terminating or Recurring | Non-terminating, Non-recurring | Both types |

| Count | Infinite | Infinite | Infinite | Infinite | Infinite | Infinite |

| Includes previous? | N/A | ⊃ N | ⊃ W ⊃ N | ⊃ Z ⊃ W ⊃ N | — | ⊃ All |

Decimal Expansion Reference

Rational Numbers – Decimal Patterns

Terminating Decimals (stop):

- 1/2 = 0.5

- 3/4 = 0.75

- 7/8 = 0.875

- 3/5 = 0.6

Non-Terminating Recurring (repeat):

- 1/3 = 0.333… = 0.3̄

- 2/3 = 0.666… = 0.6̄

- 1/6 = 0.1666… = 0.16̄

- 1/7 = 0.142857142857… = 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄

- 4/11 = 0.363636… = 0.3̄6̄

Irrational Numbers – Decimal Patterns

Non-Terminating Non-Recurring (go on forever, never repeat):

- √2 = 1.41421356237…

- √3 = 1.73205080756…

- π = 3.14159265358…

- e = 2.71828182845…

- 0.101001000100001… (designed pattern)

Formula Cheat Sheet

Converting Repeating Decimals to Fractions

For purely repeating decimals:

- Let x = 0.ā (where a repeats)

- Multiply by 10^n where n = number of repeating digits

- Subtract original equation

- Solve for x

For mixed repeating decimals:

- Let x = 0.ab̄c̄ (where c repeats, a and b don’t)

- Multiply by 10^m for non-repeating part

- Multiply by 10^(m+n) for entire part

- Subtract and solve

Worked Examples – Quick Reference

Example 1: Classify 0.125

- Answer: Rational (terminating decimal)

- Fraction: 125/1000 = 1/8

Example 2: Convert 0.3̄ to fraction

- x = 0.333…

- 10x = 3.333…

- 10x – x = 3

- 9x = 3

- x = 1/3 ✓

Example 3: Convert 0.23̄ to fraction

- x = 0.2333…

- 10x = 2.333…

- 100x = 23.333…

- 100x – 10x = 21

- 90x = 21

- x = 21/90 = 7/30 ✓

Example 4: Locate √2 on number line

- Draw square with side 1 unit

- Diagonal = √(1² + 1²) = √2

- Use compass to transfer to number line

- Mark point P at √2 ≈ 1.414

Example 5: Rationalize 1/(√3 + √2)

- Multiply by (√3 – √2)/(√3 – √2)

- = (√3 – √2)/[(√3)² – (√2)²]

- = (√3 – √2)/(3 – 2)

- = √3 – √2 ✓

Example 6: Simplify √48 + √12 – √27

- √48 = √(16×3) = 4√3

- √12 = √(4×3) = 2√3

- √27 = √(9×3) = 3√3

- Result: 4√3 + 2√3 – 3√3 = 3√3 ✓

Example 7: Find 32^(2/5)

- 32 = 2^5

- 32^(2/5) = (2^5)^(2/5) = 2^(5×2/5) = 2² = 4 ✓

Important Theorems

Theorem 1: Rational Number Criterion

A number is rational ⟺ its decimal expansion is terminating or non-terminating recurring

Theorem 2: Irrational Number Criterion

A number is irrational ⟺ its decimal expansion is non-terminating non-recurring

Theorem 3: Density of Rationals

Between any two distinct rational numbers, there exist infinitely many rational numbers

Theorem 4: Density of Irrationals

Between any two distinct rational numbers, there exist infinitely many irrational numbers

Theorem 5: Pythagorean Connections

If n is not a perfect square, then √n is irrational

Examples: √2, √3, √5, √6, √7, √8, √10, √11, √13… are all irrational

But: √1=1, √4=2, √9=3, √16=4… are all rational

Key Identities for Simplification

Square Root Identities

- √(ab) = √a · √b (a, b ≥ 0)

- √(a/b) = √a/√b (a, b ≥ 0, b ≠ 0)

- (√a + √b)(√a – √b) = a – b

- (√a + √b)² = a + b + 2√(ab)

- (√a – √b)² = a + b – 2√(ab)

Exponent Identities

- a^m · a^n = a^(m+n)

- a^m / a^n = a^(m-n)

- (a^m)^n = a^(mn)

- (ab)^m = a^m · b^m

- a^(-m) = 1/a^m

- a^(1/n) = ⁿ√a

- a^(m/n) = ⁿ√(a^m) = (ⁿ√a)^m

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Thinking √4 = ±2

Correct: √4 = 2 (we take only positive root)

Mistake 2: √(a + b) = √a + √b

Correct: √(ab) = √a · √b (only works for multiplication)

Mistake 3: Dividing by zero

Remember: In p/q, q ≠ 0 always!

Mistake 4: 0.999… ≠ 1

Correct: 0.999… = 1 exactly! (no approximation)

Mistake 5: All square roots are irrational

Correct: Perfect squares (√4, √9, √16) give rational numbers

Mistake 6: π = 22/7

Correct: 22/7 ≈ 3.142857… is a rational approximation of π, but π itself is irrational

Historical Timeline

| Year | Mathematician | Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| 400 BCE | Pythagoreans | Discovery that √2 is irrational |

| 425 BCE | Theodorus of Cyrene | √3, √5, √6… √15 are irrational |

| 287-212 BCE | Archimedes | Approximated π: 3.140845 < π < 3.142857 |

| 476-550 CE | Aryabhata | π ≈ 3.1416 (4 decimal places) |

| 800-500 BCE | Sulbasutras (India) | √2 ≈ 1.4142156… (matched modern value!) |

| 1700s | Lambert & Legendre | Proved π is irrational |

| 1870s | Cantor & Dedekind | Bijection between real numbers and number line |

| Modern | Computers | π calculated to 1.24 trillion+ decimal places |

Practice Problem Types You’ll See

Type 1: Classify Numbers

- “Is √7 rational or irrational?”

- “What type of number is 0.3̄?”

- “Is every integer a rational number?”

Type 2: Find Numbers in Between

- “Find 5 rational numbers between 1 and 2”

- “Find 3 irrational numbers between √2 and √3”

Type 3: Decimal Conversions

- Convert 0.4̄ to p/q form

- Write decimal expansion of 5/13

- Prove 0.142857142857… is rational

Type 4: Simplify Expressions

- Simplify √50 + √8 – √32

- Rationalize 2/(√5 + √2)

- Simplify (√a + √b)²

Type 5: Locate on Number Line

- Show how to mark √5 on a number line

- Represent 9.3̄ on the number line

Type 6: Exponent Problems

- Find 128^(2/7)

- Simplify 2^(1/3) × 2^(5/3)

- Show that 0.999… = 1

Memory Tricks

Remember the symbols:

- Natural numbers

- Whole numbers (W = N + zero)

- Zahlen (German) for integers

- Quotient for rational numbers

- Real numbers (includes everything)

Density:

- Between any two different points on a number line: infinite rationals + infinite irrationals exist

Decimal tells all:

- Terminating or repeating? → RATIONAL

- Goes forever, never repeats? → IRRATIONAL

Perfect squares:

- √1, √4, √9, √16, √25… are rational

- All others are irrational

Famous irrationals:

- π (circle ratio), e (nature), √2 (diagonal), φ (golden ratio)

Complete Solutions

Exercise 1.1: Rational Numbers

Question 1

Is zero a rational number? Can you write it in the form p/q, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0?

Answer:

Yes, zero is a rational number.

Proof:

Zero can be written in the form p/q where:

- p = 0

- q = any non-zero integer (1, 2, 3, -5, etc.)

Examples:

- 0 = 0/1

- 0 = 0/2

- 0 = 0/100

- 0 = 0/(-7)

Since zero satisfies the definition of a rational number (it can be expressed as a ratio of two integers with non-zero denominator), zero IS a rational number.

Note: Zero is also a whole number, an integer, and a real number. It is NOT a natural number.

Question 2

Find six rational numbers between 3 and 4.

Answer – Method 1:

Using the average method repeatedly:

- (3 + 4)/2 = 7/2 = 3.5

- (3 + 7/2)/2 = 13/4 = 3.25

- (7/2 + 4)/2 = 15/4 = 3.75

- (13/4 + 7/2)/2 = 27/8 = 3.375

- (7/2 + 15/4)/2 = 29/8 = 3.625

- (15/4 + 4)/2 = 31/8 = 3.875

Six numbers: 13/4, 27/8, 7/2, 29/8, 15/4, 31/8

Or in decimal: 3.25, 3.375, 3.5, 3.625, 3.75, 3.875

Answer – Method 2:

Using common denominator (multiply by 7, since we want 6 numbers, so denominator = 6+1 = 7):

- 3 = 21/7

- 4 = 28/7

Numbers between them: 22/7, 23/7, 24/7, 25/7, 26/7, 27/7

Six numbers: 22/7, 23/7, 24/7, 25/7, 26/7, 27/7

(In decimal: 3.14̄2̄8̄5̄7̄, 3.28̄5̄7̄1̄4̄, 3.42̄8̄5̄7̄1̄, 3.57̄1̄4̄2̄8̄, 3.71̄4̄2̄8̄5̄, 3.85̄7̄1̄4̄2̄)

Question 3

Find five rational numbers between -3/5 and 4/5.

Answer:

First, let’s convert to a common denominator. To find 5 numbers, use denominator 6+1 = 7:

- -3/5 = (-3 × 7)/(5 × 7) = -21/35 = -42/70

- 4/5 = (4 × 7)/(5 × 7) = 28/35 = 56/70

Wait, let me use simpler method. Multiply both by (5+1)/5 = 6/5:

- -3/5 = -18/30

- 4/5 = 24/30

Numbers between them:

Five numbers: -17/30, -10/30, 0, 10/30, 18/30

Simplified: -17/30, -1/3, 0, 1/3, 3/5

In decimal: -0.56̄6̄, -0.3̄, 0, 0.3̄, 0.6

Question 4

State whether the following statements are true or false. Give reasons.

Part (i): Every natural number is a whole number.

Answer: TRUE

Reason:

The set of natural numbers N = {1, 2, 3, 4, …}

The set of whole numbers W = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, …}

Every element of N is contained in W. In other words, W ⊃ N.

Examples: 1 ∈ N and 1 ∈ W; 5 ∈ N and 5 ∈ W; 100 ∈ N and 100 ∈ W

Part (ii): Every integer is a whole number.

Answer: FALSE

Reason:

Whole numbers: W = {0, 1, 2, 3, …} (non-negative only)

Integers: Z = {…, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …} (include negatives)

Negative integers are NOT in W.

Counterexample: -5 is an integer but NOT a whole number. Also: -100, -1, -1000 are integers but not whole numbers.

Part (iii): Every rational number is a whole number.

Answer: FALSE

Reason:

Whole numbers: W = {0, 1, 2, 3, …}

Rational numbers: Q = {p/q : p, q ∈ Z, q ≠ 0}

Not all rationals are in W. Many rationals lie between whole numbers.

Counterexample: 1/2 is a rational number but NOT a whole number. Also: 3/4, -5/3, 2.5, 0.3̄ are all rational but not whole numbers.

Exercise 1.2: Irrational Numbers

Question 1

State whether the following statements are true or false. Justify your answers.

Part (i): Every irrational number is a real number.

Answer: TRUE

Justification:

By definition, Real numbers R = Rational numbers ∪ Irrational numbers

The union of these two disjoint sets forms all real numbers. Therefore, every irrational number is, by definition, a real number.

Historical note: Cantor and Dedekind proved in the 1870s that every point on the real number line corresponds to exactly one real number, which is either rational or irrational.

Part (ii): Every point on the number line is of the form √m, where m is a natural number.

Answer: FALSE

Justification:

Many points on the number line correspond to numbers that are NOT square roots of natural numbers.

Counterexamples:

- The point 0 cannot be written as √m for any natural number m (since √1 = 1, √4 = 2, etc.)

- The point 1/2 is not the square root of any natural number

- The point -3 is not a square root of any natural number (square roots are always non-negative)

- The point π is not a square root of a natural number

- Points between 0 and 1 on the line

Therefore, not all points are of this form.

Part (iii): Every real number is an irrational number.

Answer: FALSE

Justification:

Real numbers = Rational numbers + Irrational numbers

Many real numbers are rational, including:

- All integers: 5, -3, 0, etc.

- All fractions: 1/2, 3/4, -5/7, etc.

- All terminating decimals: 0.5, 2.75, etc.

- All recurring decimals: 0.3̄, 1.2̄3̄, etc.

Counterexample: The number 7 is a real number but is NOT irrational (it’s rational because 7 = 7/1).

Question 2

Are the square roots of all positive integers irrational? If not, give an example of the square root of a number that is a rational number.

Answer: NO, not all are irrational.

Explanation:

Perfect squares have rational square roots!

A positive integer n is called a “perfect square” if n = k² for some positive integer k.

The square roots of perfect squares are rational (in fact, they’re natural numbers):

Examples of rational square roots:

- √1 = 1 (rational ✓)

- √4 = 2 (rational ✓)

- √9 = 3 (rational ✓)

- √16 = 4 (rational ✓)

- √25 = 5 (rational ✓)

- √36 = 6 (rational ✓)

- √49 = 7 (rational ✓)

- √64 = 8 (rational ✓)

- √81 = 9 (rational ✓)

- √100 = 10 (rational ✓)

- √121 = 11 (rational ✓)

- √144 = 12 (rational ✓)

Examples of irrational square roots:

- √2, √3, √5, √6, √7, √8, √10, √11, √12, √13, …

General Rule: √n is irrational if and only if n is not a perfect square.

Question 3

Show how √5 can be represented on the number line.

Answer:

Method: Using successive perpendiculars

Step-by-step construction:

- Start by locating √2:

- Draw a square OABC with side 1 unit

- Diagonal OB = √(1² + 1²) = √2

- Use a compass centered at O with radius OB to mark √2 on the number line

- From the point √2:

- Draw a perpendicular line of length 1 unit

- By Pythagoras: (√2)² + 1² = 2 + 1 = 3

- So the hypotenuse = √3

- Transfer this to the number line using a compass

- From the point √3:

- Draw a perpendicular line of length 1 unit

- By Pythagoras: (√3)² + 1² = 3 + 1 = 4

- So the hypotenuse = √4 = 2

- Transfer to the number line

- From the point √2:

- Draw a perpendicular line of length 2 units

- By Pythagoras: (√2)² + 2² = 2 + 4 = 6

- So the hypotenuse = √6

- Transfer to number line

OR more directly for √5:

- Draw a line segment AB of length 1 unit

- Draw a perpendicular BC of length 2 units at B

- By Pythagoras: AC = √(1² + 2²) = √(1 + 4) = √5

- Place this at point O on the number line and use a compass to mark where it intersects the number line

- That point represents √5 ≈ 2.236

Verification: 2² = 4, 3² = 9, so √5 is between 2 and 3 (closer to 2)

Exercise 1.3: Decimal Expansions

Question 1

Write the following in decimal form and say what kind of decimal expansion each has:

Part (i): 36/100

Long division: 36 ÷ 100 = 0.36

Answer: 0.36 (Terminating)

Part (ii): 1/11

Long division:

0.090909...

11)1.000000

0

10

0

100

99

1 (remainder repeats)Answer: 0.0̄9̄ or 0.090909… (Non-terminating recurring)

Part (iii): 4/1

4 ÷ 1 = 4.0

Answer: 4.0 (Terminating)

Part (iv): 13/11

Long division: 13 ÷ 11 = 1.181818…

1.181818...

11)13.000000

11

20

11

90

88

20Answer: 1.1̄8̄ or 1.181818… (Non-terminating recurring)

Part (v): 1/8

1 ÷ 8 = 0.125

0.125

8)1.000

0

10

8

20

16

40

40

0Answer: 0.125 (Terminating)

Part (vi): 400/2

400 ÷ 2 = 200.0

Answer: 200.0 (Terminating)

Question 2

You know that 1/7 = 0.142857142857… Can you predict what the decimal expansions of 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, 5/7, 6/7 are, without actually doing the long division?

Answer: YES! Using the remainder pattern

Explanation:

When we divide 1 by 7, the remainders follow a pattern: 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5, 1, 3, 2, 6, 4, 5…

This cyclic pattern repeats. The key insight: each multiple has the same remainders but starting from a different position!

Predictions:

- 1/7 = 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄ (starts with remainder 1)

- 2/7 = 0.2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄4̄ (starts with remainder 2, which is the 2nd position)

- 3/7 = 0.4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄ (starts with remainder 6… wait, let me recalculate)

Actually, the correct pattern:

- 1/7 = 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄

- 2/7 = 0.2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄4̄

- 3/7 = 0.4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄1̄

- 4/7 = 0.5̄7̄1̄4̄2̄8̄

- 5/7 = 0.7̄1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄

- 6/7 = 0.8̄5̄7̄1̄4̄2̄

Notice: The repeating block “142857” appears in each, just shifted cyclically!

Question 3

Express the following in the form p/q, where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0:

Part (i): 0.6̄

Let x = 0.666…

Then 10x = 6.666…

Subtracting: 10x – x = 6.666… – 0.666…

9x = 6

x = 6/9 = 2/3

Verification: 2 ÷ 3 = 0.666… ✓

Part (ii): 0.4̄7̄ (where 47 repeats)

Let x = 0.474747…

Since two digits repeat, multiply by 100:

100x = 47.474747…

Subtracting: 100x – x = 47.474747… – 0.474747…

99x = 47

x = 47/99

Verification: 47 ÷ 99 = 0.474747… ✓

Part (iii): 0.0̄0̄1̄ (where 001 repeats)

Let x = 0.001001001…

Since three digits repeat, multiply by 1000:

1000x = 1.001001001…

Subtracting: 1000x – x = 1.001001… – 0.001001…

999x = 1

x = 1/999

Verification: 1 ÷ 999 = 0.001001… ✓

Question 4

Express 0.9999… in the form p/q. Are you surprised by your answer? With your teacher and classmates discuss why the answer makes sense.

Answer:

Let x = 0.999…

Then 10x = 9.999…

Subtracting: 10x – x = 9.999… – 0.999…

9x = 9

x = 9/9 = 1

Therefore: 0.999… = 1

Are you surprised?

YES! It seems counterintuitive, but it’s absolutely true. The decimal 0.999… (repeating forever) is exactly equal to 1, not approximately equal.

Why does this make sense?

- Algebraically: The equation 0.999… = 1 has been proven multiple ways (shown above with algebra)

- As a limit: 0.999… = 0.9 + 0.09 + 0.009 + 0.0009 + …

This is a geometric series: Σ(9/10ⁿ) = (9/10)/(1 – 1/10) = (9/10)/(9/10) = 1 - Intuitively: If 0.999… ≠ 1, what number lies between them? There is no such number! They must be equal.

- Real number line: Two different real numbers must have a rational number between them. Since we can’t find such a number between 0.999… and 1, they are the same number!

Important lesson: A number can have more than one decimal representation!

- 0.5 = 0.4999…

- 2.3 = 2.2999…

- 7 = 6.999…

This shows why rational numbers are unique up to representation, not representation itself!

Question 5

What can the maximum number of digits be in the repeating block of digits in the decimal expansion of 1/17? Perform the division to check your answer.

Answer:

For a fraction p/q in lowest terms, the maximum length of the repeating block is q – 1 (one less than the divisor).

For 1/17: Maximum = 17 – 1 = 16 digits

Verification by long division:

1 ÷ 17 = 0.0588235294117647…

The division shows:

- Remainders: 1, 10, 15, 14, 4, 6, 9, 5, 16, 12, 2, 3, 13, 11, 7, 1

- Count: 16 distinct remainders before repeating!

Answer: 1/17 = 0.0̄5̄8̄8̄2̄3̄5̄2̄9̄4̄1̄1̄7̄6̄4̄7̄ (16 repeating digits)

Question 6

Look at several examples of rational numbers in the form p/q, where p and q are integers with no common factors other than 1, and having terminating decimal representations. Can you guess what property q must satisfy?

Answer:

Property: q must have ONLY 2 and 5 as prime factors.

In other words: q = 2^a × 5^b (for non-negative integers a and b)

Why? Because 10 = 2 × 5. Terminating decimals have a finite number of decimal places, which means they can be written with a power of 10 in the denominator.

Examples:

Terminating (q = 2^a × 5^b):

- 1/2 = 0.5 ✓ (2¹)

- 1/4 = 0.25 ✓ (2²)

- 1/5 = 0.2 ✓ (5¹)

- 1/8 = 0.125 ✓ (2³)

- 1/10 = 0.1 ✓ (2 × 5)

- 3/20 = 0.15 ✓ (2² × 5)

- 7/40 = 0.175 ✓ (2³ × 5)

Non-terminating (q has other prime factors):

- 1/3: q = 3 (has prime factor 3) → 0.3̄ (repeating)

- 1/6: q = 6 = 2 × 3 (has factor 3) → 0.1̄6̄ (repeating)

- 1/7: q = 7 (prime) → 0.1̄4̄2̄8̄5̄7̄ (repeating)

- 1/12: q = 12 = 2² × 3 (has factor 3) → 0.08̄3̄ (repeating)

Question 7

Write three numbers whose decimal expansions are non-terminating non-recurring:

Answer: (Irrational numbers)

- 0.10100100010000100000…

(Pattern: 1, then n zeros before next 1) - 0.20200200020000200000…

(Pattern: 2, then n zeros before next 2) - 0.30300300030000300000…

(Pattern: 3, then n zeros before next 3)

Other examples:

- √2 = 1.41421356…

- √3 = 1.73205080…

- √5 = 2.23606797…

- π = 3.14159265…

- e = 2.71828182…

Question 8

Find three different irrational numbers between 5/7 and 9/11:

Solution:

First, convert to decimals to find the range:

- 5/7 ≈ 0.714285…

- 9/11 ≈ 0.818181…

We need irrational numbers between 0.714… and 0.818…

Three irrational numbers:

- 0.71500500050000500000… (designed pattern with gaps)

- 0.75200200020000200000… (another designed pattern)

- 0.80100100010000100000… (yet another pattern)

Alternative approach:

- √(1/2) = 1/√2 ≈ 0.707… (too small)

- √(9/16) = 3/4 = 0.75 (rational, doesn’t count)

- (√2)/2 ≈ 0.707… (still too small)

- (7 + √5)/14 ≈ 0.730… ✓

Any three constructed numbers or known irrational between the range will work.

Question 9

Classify the following numbers as rational or irrational:

Part (i): √23

Answer: IRRATIONAL

Reason: 23 is not a perfect square. (4² = 16, 5² = 25, so √23 is between 4 and 5)

By theorem: If n is not a perfect square, then √n is irrational.

√23 = 4.79583… (non-terminating non-recurring)

Part (ii): √225

Answer: RATIONAL

Reason: 225 = 15², so √225 = 15

15 is an integer, which is also rational (15 = 15/1)

Part (iii): 0.3796

Answer: RATIONAL

Reason: This is a terminating decimal (ends after 4 decimal places)

Can be written as: 0.3796 = 3796/10000 = 949/2500

Rational numbers have terminating or recurring decimal expansions.

Part (iv): 7.478478…

This can be written as: 7.4̄7̄8̄

Answer: RATIONAL

Reason: Non-terminating but recurring (478 repeats)

Let x = 7.478478…

Then 1000x = 7478.478478…

1000x – x = 7471

999x = 7471

x = 7471/999 (rational)

Part (v): 1.101001000100001…

Answer: IRRATIONAL

Reason: Non-terminating AND non-recurring

The pattern has increasing numbers of zeros (1, 2, 3, 4, … zeros)

So it never repeats. By theorem, it’s irrational.

Exercise 1.4: Operations on Real Numbers

Question 1

Classify each as rational or irrational:

Part (i): √27/√3

Simplify: √27/√3 = √(27/3) = √9 = 3

Answer: RATIONAL (it equals 3, which is an integer)

Part (ii): √8/√2

Simplify: √8/√2 = √(8/2) = √4 = 2

Answer: RATIONAL (it equals 2)

Part (iii): 2π/7π

Simplify: 2π/7π = 2/7 (π cancels)

Answer: RATIONAL (it equals 2/7, a fraction of integers)

Part (iv): √2

Answer: IRRATIONAL (by theorem, square root of non-perfect square is irrational)

Question 2

Simplify each of the following expressions:

Part (i): (3√3 + 2√3)

Combine like terms: (3 + 2)√3 = 5√3

Part (ii): (√3 – √3)

These are exactly opposite: √3 – √3 = 0

Part (iii): (√5 + √2)(√5 – √2)

Use the identity (a + b)(a – b) = a² – b²:

= (√5)² – (√2)²

= 5 – 2

= 3

Part (iv): (√5 – √2)/(√5 + √2)

Rationalize by multiplying by (√5 – √2)/(√5 – √2):

= (√5 – √2)² / [(√5 + √2)(√5 – √2)]

= (5 – 2√10 + 2) / (5 – 2)

= (7 – 2√10) / 3

= (7 – 2√10)/3

Question 3

Recall, π is defined as the ratio of circumference to diameter. That is, π = c/d. This seems to contradict the fact that π is irrational. How will you resolve this contradiction?

Answer:

This is an excellent question! The resolution is subtle:

The Key Point: While it’s TRUE that π = c/d (ratio of circumference to diameter), we CANNOT express this as a ratio of integers.

Explanation:

- When diameter is rational: If diameter d is rational, then circumference c = πd is IRRATIONAL (because π is irrational, and irrational × rational = irrational)

- When diameter is irrational: If diameter d is irrational, then circumference c might still be rational or irrational in complex ways

- No contradiction: The ratio π = c/d is correct, but neither c nor d can both be rational (that would make their ratio rational, contradicting π being irrational)

Example:

- If d = 1 (rational), then c = π (irrational)

- If d = 2 (rational), then c = 2π (irrational)

We can NEVER find two integers p and q such that p/q = π, which is why π is irrational.

Lesson: A quantity being a “ratio” doesn’t automatically make it rational. It must be a ratio of integers specifically to be rational.

Question 4

Represent 9.3 on the number line.

Answer:

Method 1: Direct marking

- 9.3 is between 9 and 10

- Divide the segment from 9 to 10 into 10 equal parts

- Mark the 3rd division from 9

- That point represents 9.3

Method 2: Using fraction

- 9.3 = 93/10 = 9 + 3/10

- Mark point 9

- Then mark 3/10 of the distance from 9 to 10

Diagram:

←———•———————•———————•———————•———→

9 9.3 10Question 5

Rationalize the denominators of the following:

Part (i): 1/√7

Multiply by √7/√7:

= (1 × √7)/(√7 × √7)

= √7/7

= √7/7

Part (ii): 1/(√7 + √6)

Multiply by (√7 – √6)/(√7 – √6):

= (√7 – √6) / [(√7 + √6)(√7 – √6)]

= (√7 – √6) / (7 – 6)

= (√7 – √6) / 1

= √7 – √6

Part (iii): 1/(√5 + √2)

Multiply by (√5 – √2)/(√5 – √2):

= (√5 – √2) / [(√5 + √2)(√5 – √2)]

= (√5 – √2) / (5 – 2)

= (√5 – √2) / 3

= (√5 – √2)/3

Part (iv): 5/(√5 – √2)

Multiply by (√5 + √2)/(√5 + √2):

= [5(√5 + √2)] / [(√5 – √2)(√5 + √2)]

= [5√5 + 5√2] / (5 – 2)

= [5√5 + 5√2] / 3

= 5(√5 + √2)/3 or (5√5 + 5√2)/3

Exercise 1.5: Laws of Exponents

Question 1

Find:

Part (i): 2³ × 2⁵

Using law: a^m × a^n = a^(m+n)

= 2^(3+5)

= 2⁸

= 256

Part (ii): (32)^(2/5)

First: 32 = 2⁵

So: 32^(2/5) = (2⁵)^(2/5) = 2^(5×2/5) = 2² = 4

Part (iii): (1/125)^(1/3)

First: 125 = 5³

So: (1/125)^(1/3) = (1/5³)^(1/3) = (5^(-3))^(1/3) = 5^(-1) = 1/5

Part (iv): (125)^(1/3) [if this is a separate question]

125 = 5³

So: 125^(1/3) = (5³)^(1/3) = 5¹ = 5

Question 2

Find:

Part (i): (3)^(2/5)

Answer: 3^(2/5) = ⁵√(3²) = ⁵√9 = 5th root of 9 ≈ 1.552

Part (ii): (32)^(2/5)

32 = 2⁵

32^(2/5) = (2⁵)^(2/5) = 2^(10/5) = 2² = 4

Part (iii): (1/125)^(1/3)

(1/125)^(1/3) = (1/5³)^(1/3) = 1/(5³)^(1/3) = 1/5 = 1/5

Question 3

Simplify:

Part (i): 2^(1/3) × 2^(5/3)

Using law: a^p × a^q = a^(p+q)

= 2^(1/3 + 5/3)

= 2^(6/3)

= 2²

= 4

Part (ii): (3)^(2/5)

Already in simplest form: ∛(9) or 3^(2/5) ≈ 1.552

Part (iii): (1/125)^(1/3)

= 1/[125^(1/3)]

= 1/5

= 1/5

Part (iv): (125^(1/3))²

= [125^(1/3)]²

= [(5³)^(1/3)]²

= [5]²

= 25

Download Free Mind Map from the link below

This mind map contains all important topics of this chapter

Visit our Class 9 Maths page for free mind maps of all Chapters