Introduction to Euclid’s Geometry is one of the most fascinating chapters in Class 9 mathematics. This chapter takes you on a historical journey through the development of geometry from ancient civilizations to the systematic approach developed by Euclid. Rather than just learning geometry as a collection of facts, you will understand the logical foundation and reasoning behind geometric principles.

Historical Development of Geometry

Geometry in Ancient Civilizations

Geometry did not develop in isolation. Different civilizations across the world contributed to its growth, each in their own unique way.

Indus Valley Civilization (3000 BCE)

The excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro reveal that the Indus Valley Civilization was remarkably advanced in geometry and practical arithmetic. The cities were highly organized with:

- Parallel roads running in specific patterns

- Underground drainage systems

- Houses with multiple rooms designed with precision

- Kiln-fired bricks with standardized dimensions

The ratio of length to breadth to thickness of the bricks used was 4 : 2 : 1, showing that these ancient people had mastered standardization and proportional thinking.

Ancient India: The Sulbasutras (800 BCE to 500 BCE)

The Sulbasutras were manuals of geometrical constructions used in ancient India. The geometry of the Vedic period developed specifically for constructing altars and fireplaces for performing Vedic rites. These constructions had to follow precise shapes and areas to be considered effective instruments.

Types of altars included:

- Square altars – for household rituals

- Circular altars – for household rituals

- Complex altars – combinations of rectangles, triangles, and trapeziums for public worship

One imp example is the Sriyantra mentioned in the Atharvaveda, which consists of nine interwoven isosceles triangles arranged to produce 43 subsidiary triangles. Though accurate geometric methods were used, the mathematical principles behind these constructions were not formally discussed or proven.

Geometry in Other Civilizations

Babylonia and Egypt: Geometry was practical and applied to daily needs. In Egypt, geometry consisted mainly of statements of results without general rules of procedure. Neither civilization developed geometry as a systematic science.

Greece: The Greeks took a revolutionary approach. They were interested in understanding the reasoning behind geometric constructions and establishing truth through deductive reasoning rather than just practical application.

The Greek Contribution: From Practical to Theoretical

Thales (640 BCE – 546 BCE)

Thales is credited with giving the first known mathematical proof. His famous proof demonstrated that a circle is bisected (cut into two equal parts) by its diameter. This was a turning point in mathematical history because he didn’t just state the fact—he proved it logically.

Pythagoras (572 BCE) and His School

One of Thales’ most famous pupils was Pythagoras. Pythagoras and his group discovered many geometric properties and developed the theory of geometry extensively. You have already learned about the Pythagorean theorem, which states that in a right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of squares of the other two sides.

Development of Systematic Geometry

This process of development continued for about 272 years (from around 572 BCE to 300 BCE), with mathematicians gradually building a systematic framework for geometric knowledge.

Euclid (300 BCE)

By 300 BCE, Euclid, a teacher of mathematics at Alexandria in Egypt, collected all the known geometric work and organized it in his famous treatise called the “Elements” (Stoicheia in Greek). This 13-volume work became the foundation for all geometry teaching for over 2000 years. Even today, Euclid’s approach influences how geometry is taught.

Undefined Terms in Geometry

Why Some Terms Remain Undefined

Euclid provided definitions for geometric terms, but mathematicians have recognized that some of these definitions themselves refer to undefined concepts. For example, Euclid defined a point as “that which has no part.” But this definition is circular because it refers to the idea of “having parts,” which itself needs to be defined.

Similarly, a line was defined as “breadth-less length,” but this definition requires understanding “breadth” and “length,” which are also not defined.

The Three Undefined Terms

Because of this logical issue, in modern geometry we take three terms as undefined:

- Point – We represent it as a dot, though intuitively we know a dot has dimension

- Line – A straight path extending infinitely in both directions

- Plane – A flat surface extending infinitely in all directions (Euclid called it a “plane surface”)

These terms are not defined but can be understood intuitively through physical models and examples.

Axioms and Postulates: The Foundation of Geometry

What are Axioms and Postulates?

Euclid assumed certain properties that did not need to be proved. These are obvious universal truths that serve as the foundation for building all geometric knowledge.

Euclid divided these assumptions into two categories:

- Axioms (also called Common Notions) – Assumptions that apply throughout mathematics, not specifically to geometry alone

- Postulates – Assumptions specific to geometry

Euclid’s Axioms

Here are seven of Euclid’s axioms (not in his original order):

Axiom 1: Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to one another.

Example: If the area of triangle A = area of rectangle B, and area of rectangle B = area of square C, then area of triangle A = area of square C.

Axiom 2: If equals are added to equals, the wholes are equal.

Algebraically: If a = b and c = d, then a + c = b + d

Axiom 3: If equals are subtracted from equals, the remainders are equal.

Algebraically: If a = b and c = d, then a – c = b – d

Axiom 4: Things which coincide with one another are equal to one another.

This axiom justifies the principle of superposition (overlapping two figures to check if they are congruent). If two figures coincide exactly, they are equal.

Axiom 5: The whole is greater than the part.

Mathematically: If quantity B is a part of quantity A, then A > B. In other words, A = B + C for some positive quantity C.

This is considered a universal truth because it applies to all magnitudes and quantities, not just geometric figures.

Axiom 6: Things which are double of the same things are equal to one another.

Algebraically: If a = b, then 2a = 2b

Axiom 7: Things which are halves of the same things are equal to one another.

Algebraically: If a = b, then a/2 = b/2

Imp Note about Magnitudes

Magnitudes of the same kind can be compared and added together. However, magnitudes of different kinds cannot be compared. For example:

- A line cannot be compared to a rectangle

- An angle cannot be compared to a pentagon

- A length cannot be compared to an area

Euclid’s Postulates

Postulates are assumptions specific to geometry that we accept as true without proof. Here are Euclid’s five postulates:

Postulate 1: A straight line may be drawn from any one point to any other point.

This means there is always a unique line connecting any two distinct points.

Postulate 2: A terminated line can be produced indefinitely.

A “terminated line” means a line segment (with definite endpoints). This postulate says we can extend a line segment indefinitely in either direction to form a complete line.

Postulate 3: A circle can be drawn with any centre and any radius.

Given any point as center and any length as radius, we can always draw a circle.

Postulate 4: All right angles are equal to one another.

Every right angle (90°) is equal to every other right angle.

Postulate 5: If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side of the transversal together less than two right angles, then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the sum of angles is less than two right angles.

This is the famous parallel postulate, which is more complex than the others. It essentially deals with parallel lines and angles formed by a transversal.

Theorems: Statements to be Proved

A theorem is a statement that is proved using:

- Definitions

- Axioms and postulates

- Previously proved theorems

- Deductive reasoning

Theorem 5.1: Two Distinct Lines Cannot Have More Than One Point in Common

Given: Two lines l and m

To Prove: They have only one point in common

Proof:

Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that two distinct lines intersect at two different points, P and Q.

If two lines pass through two distinct points P and Q, this contradicts Postulate 1, which states that only one line can pass through two distinct points.

Since this assumption leads to a contradiction, our assumption must be wrong.

Therefore, two distinct lines cannot have more than one point in common. They can intersect at most at one point.

This proof uses the method of proof by contradiction (also called indirect proof or reductio ad absurdum).

EXERCISE 5.1 – Complete Solutions

Question 1

Problem: Which of the following statements are true and which are false? Give reasons for your answers.

(i) Only one line can pass through a single point.

Answer: FALSE

Reason: Infinitely many lines can pass through a single point. From any point, we can draw lines in all directions. For example, think of a point on a paper—we can draw horizontal lines, vertical lines, diagonal lines, and lines at any angle through that point.

(ii) There are an infinite number of lines which pass through two distinct points.

Answer: FALSE

Reason: Through two distinct points, exactly one unique line can pass. This is stated in Postulate 1: “A straight line may be drawn from any one point to any other point.” Only one line connects any two distinct points; no more, no less.

(iii) A terminated line can be produced indefinitely on both the sides.

Answer: TRUE

Reason: This is directly stated in Postulate 2. A terminated line (line segment) can be extended indefinitely on both sides to form a complete line.

(iv) If two circles are equal, then their radii are equal.

Answer: TRUE

Reason: If two circles are equal (meaning they have the same radius and can be superimposed perfectly), then by definition their radii must be equal. Equal circles have equal radii.

(v) In Fig. 5.9, if AB = PQ and PQ = XY, then AB = XY.

Answer: TRUE

Reason: This follows from Axiom 1: “Things which are equal to the same thing are equal to one another.” Since AB equals PQ, and PQ equals XY, then AB equals XY. This is the transitive property of equality.

Question 2

Problem: Give a definition for each of the following terms. Are there other terms that need to be defined first? What are they, and how might you define them?

(i) Parallel Lines

Definition: Two lines in the same plane are parallel if they do not intersect, no matter how far they are extended in either direction.

Prerequisite Terms to Define First:

- Line (undefined term – must be understood intuitively)

- Plane (undefined term – must be understood intuitively)

- Intersection – two lines intersect if they meet at a point

Alternative Definition: Two lines are parallel if they are equidistant from each other at all points.

(ii) Perpendicular Lines

Definition: Two lines are perpendicular if they intersect at a right angle (90 degrees).

Prerequisite Terms to Define First:

- Line (undefined term)

- Intersection – where two lines meet

- Right angle – an angle of 90 degrees

- Angle – formed by two rays with a common endpoint

Symbol Used: l ⊥ m (read as “l is perpendicular to m”)

(iii) Line Segment

Definition: A line segment is the part of a line that lies between two distinct points on the line, including the two endpoints.

Prerequisite Terms to Define First:

- Line (undefined term)

- Point (undefined term)

- Endpoints – the two points marking the ends of a segment

Symbol Used: AB denotes the line segment from point A to point B

Imp Note: A line segment is “terminated” (has definite endpoints), unlike a line which extends infinitely.

(iv) Radius of a Circle

Definition: The radius of a circle is the distance from the center of the circle to any point on the circle.

Prerequisite Terms to Define First:

- Circle – the set of all points at a fixed distance from a given point

- Center – the fixed point from which all points on the circle are equidistant

- Distance – the length of the line segment joining two points

Imp Note: All radii of the same circle are equal in length.

(v) Square

Definition: A square is a quadrilateral (four-sided figure) with all four sides equal in length and all four angles equal to 90 degrees (right angles).

Prerequisite Terms to Define First:

- Quadrilateral – a polygon with four sides and four vertices

- Side – one of the line segments forming the polygon

- Right angle – an angle measuring 90 degrees

- Equal – having the same measure or length

Imp Properties:

- All sides are equal (AB = BC = CD = DA)

- All angles are right angles (90° each)

- Diagonals are equal and bisect each other at right angles

- It is a special case of both rectangle and rhombus

Question 3

Problem: Consider two postulates given below:

(i) Given any two distinct points A and B, there exists a third point C which is in between A and B.

(ii) There exist at least three points that are not on the same line.

Do these postulates contain any undefined terms? Are these postulates consistent? Do they follow from Euclid’s postulates? Explain.

Answer:

Undefined Terms: Yes, these postulates contain undefined terms:

- Point – undefined term (we have only intuitive understanding)

- Between – not formally defined in the postulates given, but relies on intuitive understanding of betweenness

Consistency: Yes, these postulates are consistent with each other. They do not contradict each other. Postulate (i) can be true while postulate (ii) is also true at the same time.

Do they follow from Euclid’s postulates?

- Postulate (i) does NOT explicitly follow from Euclid’s postulates. Euclid’s postulates do not directly address whether points exist between two given points. However, this idea is implicit in geometric thinking.

- Postulate (ii) also does NOT directly follow from Euclid’s postulates, but it is a reasonable assumption because Euclid’s postulates assume the existence of at least a two-dimensional plane.

Explanation: These are reasonable geometric assumptions, but they are not necessary consequences of Euclid’s original postulates. They are additional assumptions that could be added to Euclid’s system to create a more complete geometric framework. In modern geometry, similar ideas are formally incorporated into the axiomatic system.

Question 4

Problem: If a point C lies between two points A and B such that AC = BC, then prove that (1/2)AC = (1/2)AB. Explain by drawing the figure.

Answer:

Given:

- Point C lies between points A and B

- AC = BC (C is the midpoint of AB)

To Prove: (1/2)AC = (1/2)AB

Proof:

Since C lies between A and B, we can write: AB = AC + CB

But we are given that AC = BC, so: AB = AC + AC AB = 2AC

Dividing both sides by 2: AB/2 = 2AC/2 AB/2 = AC

Or written differently: (1/2)AB = AC

Therefore: (1/2)AC = (1/4)AB…

Wait, let me reconsider. The problem asks to prove (1/2)AC = (1/2)AB, which seems unusual. Let me interpret this as proving AC = (1/2)AB.

Correct Solution:

Given: C is between A and B with AC = BC

To Prove: AC = (1/2)AB

Since C is between A and B: AB = AC + CB

Since AC = CB (given): AB = AC + AC = 2AC

Dividing both sides by 2: AC = AB/2

Or: AC = (1/2)AB ✓

Figure:

A ─────────── C ─────────── B

AC BC

AC = BC (C is midpoint)

Question 5

Problem: In Question 4, point C is called a midpoint of line segment AB. Prove that every line segment has one and only one midpoint.

Answer:

Given: A line segment AB

To Prove: There exists exactly one point C on AB such that AC = CB

Proof:

Existence (that a midpoint exists):

Consider the line segment AB. By Postulate 3, we can draw a circle with center A and radius r (where r is some length). We can also draw another circle with center B and the same radius r.

For a suitable choice of r (specifically, r = AB/2), these circles will intersect at exactly one point C on the segment AB, and this point C will be such that AC = BC.

Therefore, a midpoint exists.

Uniqueness (that only one midpoint exists):

Suppose there are two midpoints, C and D, on segment AB such that:

- AC = CB (C is a midpoint)

- AD = DB (D is a midpoint)

Without loss of generality, assume C is to the left of D on the segment.

From AC = CB: AB = AC + CB = 2AC So, AC = AB/2

From AD = DB: AB = AD + DB = 2AD So, AD = AB/2

This means AC = AD = AB/2

Since C and D are both at distance AB/2 from A, they must be at the same location.

Therefore, C = D.

This proves that every line segment has one and only one midpoint. ✓

Question 6

Problem: In Fig. 5.10, if AC = BD, then prove that AB = CD.

A ─── C ─── B ─── D

Answer:

Given:

- Four collinear points A, C, B, D (in that order)

- AC = BD

To Prove: AB = CD

Proof:

From the figure, we can see that points are arranged as: A, then C, then B, then D.

We can write:

- AB = AC + CB (since C is between A and B)

- CD = CB + BD (since B is between C and D)

Now, from the first equation: CB = AB – AC … (equation 1)

From the second equation: CD = CB + BD … (equation 2)

Substituting equation 1 into equation 2: CD = (AB – AC) + BD CD = AB – AC + BD

We are given that AC = BD, so: CD = AB – AC + AC CD = AB

Therefore: AB = CD ✓

Alternative Proof using Axioms:

Given: AC = BD

We need to prove: AB = CD

AB = AC + CB CD = CB + BD

Since AC = BD (given), by adding CB to both sides (Axiom 2: if equals are added to equals): AC + CB = BD + CB AB = CD ✓

Question 7

Problem: Why is Axiom 5, in the list of Euclid’s axioms, considered a ‘universal truth’? (Note that the question is not about the fifth postulate.)

Answer:

Axiom 5 states: “The whole is greater than the part.”

Why it is a universal truth:

- Applies everywhere: This axiom applies to all types of magnitudes—lengths, areas, volumes, quantities, numbers, and any measurable entity. It is not limited to just geometric figures.

- Self-evident: The truth of this statement is immediately obvious and doesn’t require any proof. Any part of a whole is necessarily smaller than the whole itself.

- Logical foundation: This axiom is fundamental to establishing the concept of “greater than” and “less than.” Without this axiom, we couldn’t properly define inequality relationships.

- Never contradicted: In the entire realm of mathematics and real-world experience, this statement is never violated. You can never find a part that is larger than its whole.

- Intuitive understanding: Even without formal mathematical training, any person understands that a piece of something is smaller than the complete thing. For example:

- A slice of pizza is less than a whole pizza

- A part of a journey is less than the complete journey

- A portion of a salary is less than the entire salary

- Algebraic representation: Mathematically, if B is a part of A, then A can be written as: A = B + C (where C is some positive quantity) From this: A > B (always)

- Cross-disciplinary: This truth holds in physics, chemistry, biology, economics, and all fields where magnitudes are compared. This makes it truly universal.

Conclusion: Axiom 5 is considered a universal truth because it applies across all mathematics and all domains of knowledge, is self-evident, never contradicted, and forms the logical basis for inequality relationships.

Why Euclid’s Geometry Matters

- Historical Significance: For over 2000 years, Euclid’s Elements was the primary textbook for geometry worldwide

- Logical Foundation: It established the importance of proving statements rather than just stating them

- Systematic Approach: It showed how all geometric knowledge could be built from a few fundamental assumptions

- Modern Relevance: Even modern geometry is based on the axiomatic approach developed by Euclid

- Philosophical Impact: It influenced how mathematics and science approach truth and proof

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Confusing Axioms with Postulates: Remember, axioms are universal truths; postulates are geometry-specific

- Assuming undefined terms have formal definitions: Point, line, and plane have only intuitive meanings

- Not using correct notation: Use AB for a line through A and B, and use AB for the length of segment

- Forgetting the uniqueness in proofs: When proving uniqueness, show not just that something exists, but that only one such thing exists

- Missing steps in logical reasoning: Every step in a proof must be justified using axioms, postulates, or previously proved theorems

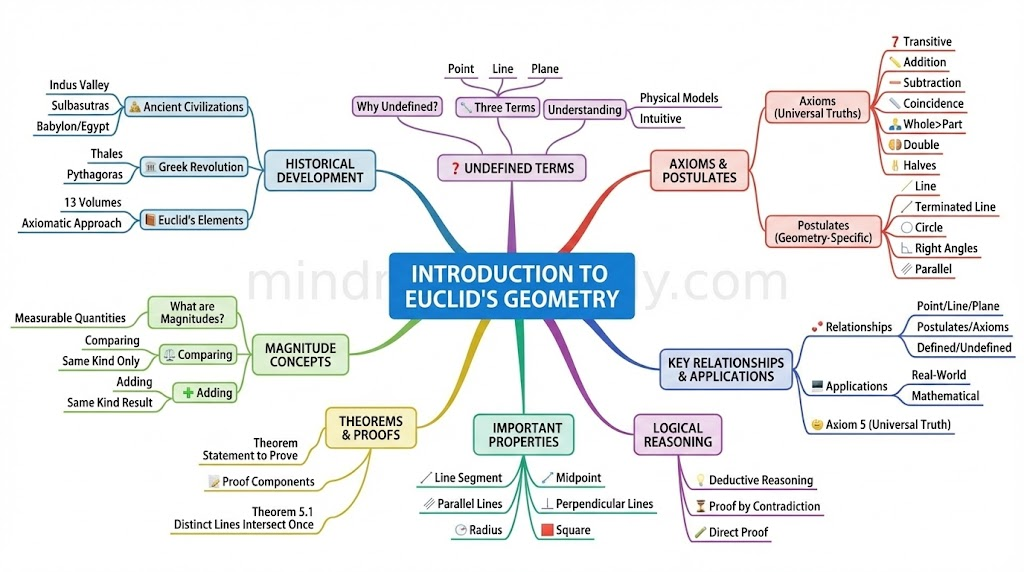

Download Free Mind Map from the link below

This mind map contains all important topics of this chapter

Visit our Class 9 Maths page for free mind maps of all Chapters